Easily the most beloved accounts in the Bible is the account of David and Goliath. So compelling and well-known is the drama that it has become the primary historical metaphor in Western culture for describing any individual or group who overcomes seemingly insurmountable odds to defeat an oppressor.

Easily the most beloved accounts in the Bible is the account of David and Goliath. So compelling and well-known is the drama that it has become the primary historical metaphor in Western culture for describing any individual or group who overcomes seemingly insurmountable odds to defeat an oppressor.

But the biblical narrative is not primarily a story about human courage and effort; instead, it is about the awesome power of a life built around bold faith in the Lord and ultimately it points us to Jesus. McCarter states, “It is Yahweh who gives victory, and he may give it to the weak (Israel) in order that his power might be known to all.”

The popularity and power of this historical account from David’s life is not accidental. The writer deliberately employed certain narrative techniques that cause this story to achieve special prominence in the reader’s/listener’s mind. First of all, he made the account longer than any other Davidic narrative relating to a single battle with a foreign enemy (912 words in Hebrew). Second, he placed more quotations in it than in other stories (twenty-two), including the longest quotation in 1, 2 Samuel placed on the lips of a named foreigner (Goliath, thirty-three words; 17:8–9). He also provided descriptions of normally omitted aspects of the narrative; for example, the pieces and weight of Goliath’s armor, the number of cheeses and loaves of bread brought to the commander, the process of David’s acquisition of sling stones, and David’s removal of a sword from its scabbard. Furthermore, the account contains details that create apparent tensions with its narrative context: for example, David’s absence from Saul’s court after he was made a permanent courtier (v. 17; cf. 16:22) and Saul’s nonrecognition of David (v. 55; cf. 16:21). These details force the reader to ponder the narrative after its reading and thus make the story more memorable and more likely to be studied further. 2

17:1–3 We cannot know how soon the events of this chapter occurred after the previous events. However, enough time must have passed for Saul to have changed his policy toward David, permitting him to return to Bethlehem. It also may have been long enough for the youthful David to mature and change significantly in appearance, though not long enough for David to have become old enough for military service (=age twenty; cf. Num 1:3; also 1 Sam 17:33).

As this account opens, the Philistines had assembled their army in the west frontiers of Judah about eight miles east of Gath and fifteen miles west of Bethlehem, and then “pitched camp” two miles west of Socoh at “Ephes Dammim.” Though no free-flowing water exists here, the camp’s proximity to a major Philistine city meant that provisions would not be a problem for Israel’s enemy.

In response to the Philistine invasion, Saul’s army assembled in the Valley of Elah (v. 2; lit., “Valley of the [cultically significant] Tree”), directly opposite the Philistine camp. Separating the two camps geographically was a wadi, a usually dry river bed. Separating the Israelites from the Philistines psychologically, as the following verses indicate, was a chasm of fear.

17:4–7 Among the Philistine ranks was a remarkable soldier named Goliath, a name of possibly Hittite or Lydian origin. He was a “man between the two” (NIV, “champion”). This phrase, used only here in the Old Testament, apparently refers to an individual who fought to the death in representative combat with an opponent from a foreign army. One-on-one combat as a substitute for combat between two full armies apparently was not regularly practiced in Semitic societies; it probably was more commonly employed by the Philistines.3

Goliath’s most remarkable featue was his height; he was (lit.) “six cubits and a span” (= nine feet, nine inches) tall. Whether this measure refers to Goliath in or out of uniform is immaterial; his physical stature was awesome and psychologically overpowering, especially to the typically small Israelites.

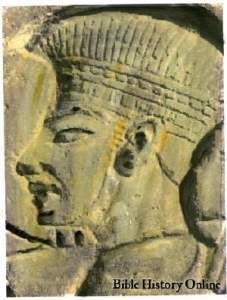

Adding to Goliath’s overwhelming appearance as a fighter was his combat gear. At a time when most Israelite soldiers wore only basic clothing in battle (cf. 13:22), Goliath was sheathed in metal. His head was covered with “a bronze helmet” (v. 5). In ancient  Egyptian artwork Philistine soldiers are depicted wearing a feathered headdress, not a helmet;50 Goliath’s headgear therefore was apparently atypical, designed for the special needs of representative combat. Protecting his trunk was “a coat of scale armor weighing five thousand shekels” (= 126 pounds). Completing his body armor were “bronze greaves” (v. 6) or knee and shin protectors. A covering of this weight and composition would have drastically reduced Goliath’s ability to respond with quickness and agility in close combat and suggests that he did not expect a skirmish involving hand-to-hand combat.

Egyptian artwork Philistine soldiers are depicted wearing a feathered headdress, not a helmet;50 Goliath’s headgear therefore was apparently atypical, designed for the special needs of representative combat. Protecting his trunk was “a coat of scale armor weighing five thousand shekels” (= 126 pounds). Completing his body armor were “bronze greaves” (v. 6) or knee and shin protectors. A covering of this weight and composition would have drastically reduced Goliath’s ability to respond with quickness and agility in close combat and suggests that he did not expect a skirmish involving hand-to-hand combat.

Goliath’s weaponry was as overwhelming in appearance as his height and armor. He had “a bronze scimitar” (Hb. kîdôn; NIV, “javelin”), a curved sword, “slung on his back.” In addition, he had a spear whose “shaft was like a weaver’s rod.” This description may relate to the size and weight of the spear’s shaft or, more probably, to the fact that it had a loop of cord attached to it.51 At the head of Goliath’s spear was a massive “iron point” that weighed “six hundred shekels” (= 15.1 lbs.). Iron was the preferred metal for implements of warfare because it was strong, nonmalleable, and could retain a sharp edge much better than bronze. A weapon of this massive weight, while intimidating in appearance, would have been quite awkward to use; it was apparently designed mainly to intimidate.

As if all this were not enough, Goliath also had a “shield bearer” who “went ahead of him.” Two primary styles of shields were used in ancient Near Eastern warfare; a smaller, round shield (Hb. māgēn) and a larger, rectangular body shield (ṣinnâ). Goliath’s assistant protected him with the second type.

This passage presents the longest description of military attire in the Old Testament. Goliath’s physical stature, armor, weaponry, and shield bearer must have made him appear invincible. However, the reader has just been warned against paying undue attention to outward appearances. The detailed description of Goliath’s external advantages here suggests that chap. 17 was intended in part to serve as an object lesson in the theology of the previous chapter (cf. 16:7).

This passage presents the longest description of military attire in the Old Testament. Goliath’s physical stature, armor, weaponry, and shield bearer must have made him appear invincible. However, the reader has just been warned against paying undue attention to outward appearances. The detailed description of Goliath’s external advantages here suggests that chap. 17 was intended in part to serve as an object lesson in the theology of the previous chapter (cf. 16:7).

17:8–11 As Goliath stepped forth between the two armies, he spoke insolently to the Israelites. First, he questioned their resolve in defending themselves against the army now camped on their lands: if they were unwilling to engage in combat with Goliath, why did they line up for battle? (v. 8).

Second, he educated them concerning the practice of representative combat. The concept was simple: a soldier chosen from the Israelite ranks was to fight to the death with Goliath. The results of the high-stakes contest were also clear-cut: the nation represented by the dead soldier would become subject to the nation represented by the victor. The fact that Goliath is recorded as explaining the practice to the Israelites suggests that they had not previously participated in a contest like this; the fact that the Philistines later reneged on the agreement (cf. 18:30) suggests that representative combat was not taken seriously even by those who advocated it.

Third, Goliath insulted the Israelites: “I heap shame on [Hb. ḥrp; NIV, “defy”] the ranks of Israel!” The giant’s dramatic presentation, complete with costume, actions, and words, achieved its desired effect: “Saul and all the Israelites were dismayed and terrified” (v. 11; cf. also Deut 1:21; 31:8; Josh 8:1; 10:25; 2 Chr 20:15, 17; 32:7; Isa 51:7; Ezek 2:6).

17:12–15 The narrative focus shifts to David, who is reintroduced to the reader in this section. Here David’s genealogical record is stated explicitly for the first time—it was only implicit prior to this point. Ephrathah, an important matriarch in the Judahite clan (cf. 1 Chr 2:19; 4:4), was the mother of Hur, who was an influential figure in the history of Bethlehem, and a relative of Jesse.

“Jesse had eight sons,” and “David was the youngest” (v. 14); these assertions are in tension with 1 Chr 2:13, though not contradicted by it. Though 1 Chr 2:13 notes only seven sons of Jesse and states that David was the seventh, the differences between the passages may simply be a matter of reckoning. If Jesse had a son who died, especially one who died as a minor, the Chronicler’s omission of that son could merely be the result of a difference in criteria for inclusion in the genealogical record.

Jesse “was old and well advanced in years” (v. 12) at the time of this Philistine incursion into Judahite territory. Consequently, he was exempted from military service. His sending only “the three oldest” (v. 14) of his sons to serve in Saul’s army suggests one or both of two possibilities. The other sons, including David, may have been under the age of twenty, the minimum age for military service in Israel (cf. Num 1:3, 19); or perhaps families were required to provide no more than three sons for military service, in which case the three eldest would have been given preference for this task.4

Though David had earlier been called a warrior (16:18) and was made a permanent courtier (16:22), he was denied a role in Saul’s army assembled at the Valley of Elah. Instead he played a support role, “going back and forth from Saul” (v. 15) in short-term stints (note his use of a tent for a temporary residence, v. 54) that required David to be gone perhaps as little as one night (cf. v. 54). David’s responsibilities within Saul’s army may have been reduced when three of Jesse’s other sons went on active duty. This certainly would have helped Jesse, who needed David to “tend his … sheep” now that the other sons had to be away for a lengthy period of time.

17:16–24 The standoff between the encamped armies of the Philistines and Israelites continued for at least “forty days” (v. 16), a situation that would have strained the resources of the impoverished Israelite monarchy. This lengthy standoff also would have made life difficult for individual Israelite families since this event would have occurred during the spring or summer, when adult males would have been needed for agricultural chores. At the beginning and end of each day during that time, Goliath stepped forward to taunt the Israelites.

The families of the soldiers supplied the rations for their relatives and others in the ranks. David bore the responsibility of transporting the foodstuffs to his three brothers as well as “the leader of the thousand” (“commander of their unit”). Meat, a rarity in the typical ancient Israelite diet, was not included among the provisions.

Jesse also asked David to check to see how the patriarch’s sons were faring and to “take their token” (NIV, “bring back some assurance from them”). The “token” (Hb. “ʿarubbâ) probably was a form of compensation given to families who helped underwrite the army’s expenses, perhaps a sort of promissory note redeemable for a certain portion of plunder that might be taken from the Philistines in the event of an Israelite victory; alternatively, it was “to confirm the safe delivery of the gifts and that his brothers are still alive.”

At the first sign of morning light on the horizon David “left the flock with a shepherd.” The inclusion of this subtle detail in the text highlights the fact that David was a “good shepherd”—a significant metaphorical image of a good leader (cf. John 10:1–21)—and increases the contrast between David and Saul (cf. previous notes on chap. 9).

Though the journey exceeded fifteen miles, David arrived at the Israelite camp early in the morning, “as the army was going out to its battle positions shouting the war cry” (v. 21; cf. Josh 6:16) but avoiding any open conflict. Matching the Israelites’ movements were the Philistines, who “were drawing up their lines” to create a standoff. Dutifully, David first handed the provisions over to the supply officer and then “ran to the battle lines” and “checked on his brothers’ condition” (v. 22; NIV, “greeted his brothers”).

Being on the front lines at this hour of the morning, David was able to witness Goliath, “the champion from Gath” (v. 23), as he took his place between the two armies. David heard Goliath’s words, and perhaps for the first time in his life he heard the Lord being ridiculed. David also saw his fellow Israelites’ reactions to this desecration: “they all ran from him in great fear” (v. 24).

17:25–30 Word had been spread among the soldiers that Saul had determined that Israel should take up Goliath’s challenge. Though the king would not personally fight the giant, he would handsomely reward anyone who successfully did so. The offer to “give him his daughter in marriage” (v. 25) was particularly appealing, for it would provide access to additional, unnamed privileges reserved for the royal household.

David was deeply disturbed that a Philistine, who was uncircumcised and therefore outside of a covenant relationship with the Lord, would so boldly heap shame on (NIV, “defy”; v. 26) “the armies of the living God.” Goliath’s words were not just an insult directed against the Israelite army; they were also an assault on “the living God,”54 since the army was composed of members of the Lord’s covenant community. Having missed out on the details of the king’s response to Goliath because of his duties in Bethlehem, David asked for and received further information from “the men standing near him” (v. 26).

David’s interest in this matter proved irritating to Eliab, perhaps because of his fear of Goliath, and he caustically accused David of having a haughty and wicked heart that motivated him to abandon his duty to the family’s livestock for the sake of watching others die in battle. Of course, Eliab’s accusation was false. The author perhaps included it in the narrative to demonstrate the correctness of the Lord’s decision to reject Eliab as Israel’s next king (cf. 16:7). Like Eli and Saul, Eliab lacked the ability to make proper judgments about others—his “heart” was not right. Eliab’s harsh words against his younger brother also strengthen the parallels that exist between David and Joseph, a young man in the Torah who also experienced family criticism prior to saving the Israelites (cf. Gen 37:8).

The concluding clause of David’s response to Eliab is brief but problematic. The literal Hebrew—“[Is] it not [a] word/matter?”—is translated variously by major contemporary versions: NKJV: “Is there not a cause?” NRSV: “It was only a question”; NIV: “Can’t I even speak?” I am inclined to translate David’s response to Eliab loosely in the following way: “What have I done to offend you now? I happen to have been asking about a very important matter.” Having ended his brief conversation with Eliab, David returned to his investigation of the matter and received confirmation of the details.

17:31–37 David’s outrage sparked by Goliath’s blasphemies, as well as his keen interest in the particulars of the royal offer, did not escape the attention of others. Details of David’s reaction were even “reported to Saul, and Saul sent for him” (v. 31).

David’s words to the king express youthful idealism in its full flower. First he exhorted those around him—all of whom were older than he—to stop being disheartened (lit., “Let not the human heart fall”). Then he proposed an astonishing solution to Israel’s dilemma: he himself would “go and fight” Goliath.

Saul immediately rejected David’s offer. Then, speaking with the battle-tested voice of reason, he reminded David of some obvious but apparently overlooked facts: “You are only a boy, and he has been a fighting man from his youth” (v. 33). Saul’s reference to David’s adolescence suggests that David was under twenty years of age, the earliest age at which an Israelite was permitted to serve in the military (cf. Num 1:3; 26:2).

Saul’s royal rejection of David’s offer should have concluded the meeting. However, David’s idealism was exceeded only by his determination and his faith in the Lord. Consequently, he continued his efforts to change the king’s heart. This time David dropped his sermonizing, choosing instead to emphasize his credentials and experience: literally, “[A] shepherd was your servant” (v. 34) who had already been victorious in two previous mortal combats, one with a lion and one with a bear. In each case David “went after” the marauding beast and “struck it.” Then, when the enraged animal “turned on” David, he “seized it by its hair, struck it, and killed it.”

To David’s way of thinking, “the uncircumcised Philistine” had reduced himself to the level of a brutish animal “because he … defied the armies of the living God” (v. 36). Thus, fighting Goliath would be just another fight with a wild beast. The Lord had delivered David “from the hand [“paw”] of the lion and the hand [“paw”] of the bear,” and he would deliver him “from the hand of this Philistine” (v. 37).

David’s faith and courage were as extraordinary as his logic was simple. The king, disarmed by David’s impressive presentation, decided to make what was perhaps the greatest military gamble of his career and accept David’s offer. In a word of blessing that was certainly also a prayer, Saul asked that “the Lord be with” David in his fight.

17:38–40 In addition to the prayerful blessing, Saul also gave David the use of Israel’s finest offensive and defensive military gear, the king’s own. Saul’s battle gear included a basic “tunic” worn next to the skin, “a coat of armor” worn over the cloth garment,55 a helmet, and a sword.

David allowed Saul to put the armor on him. Ironically, Saul’s actions confirmed and foreshadowed the royal status God promised David: the Lord had clothed David with the Spirit that enabled kingship; now Saul clothed David with the symbols that exemplified kingship. Yet David was unable to grow accustomed to Saul’s military gear, and he removed it. The writer’s inclusion of the clothing incident probably was meant to serve two functions: first, to preserve an unusual but interesting occurrence in the background of the Goliath event, indicating the greater value of divine enablement over human devices; second and more importantly, to symbolize David’s rejection of Saul’s approach to kingship. Saul chose to dress in royal clothing “such as all the other nations have”; David would wear none of it. Instead, he would identify with the great shepherd-leaders of the Torah—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and especially Moses—and live by faith in the promises of God (cf. Heb 11).

Accordingly, David armed himself as a shepherd would have, with a stick and a sling. He “took his staff in his hand” (v. 40). The stick, while a crude weapon, could have afforded some protection in close combat. David also took some stones from the bottom of the wadi. Because the stones were intended for use “with his sling” in battle, they probably were about the size of typical ancient Near Eastern slingstones—as big as tennis balls.5

The weapons David gathered for use against Goliath—the stick and the stones—were not products of human artifice; rather, they were shaped by God. As such, the author may have included these details as a counterpoint to 13:19–22; the Philistines feared and relied on weapons pulled from human forges, but David would conquer them with divinely manufactured weapons. Armed with these provisions, David “approached the Philistine.”

17:41–44 The events of the fatal confrontation now unfold rapidly as Goliath and his shield bearer advanced toward David. As Goliath drew near, he noticed for the first time the details of his opponent. Looking David in the face, he “saw that he was only a boy, ruddy and handsome” (v. 42). Winning a contest against a crudely armed, underage challenger would not be particularly prestigious for the Philistine giant, “and he despised” David.

In order to make the most of the contest, however, Goliath began a psychological assault. First, he insulted David’s most prominent weapon—the stick in his hand, suggesting that it was an instrument fit only for spanking a dog. Next, he “cursed David by his gods” (v. 43). The author’s use of the term “cursed” (Hb. qālal) here is theologically significant;57 readers knowledgeable of the Torah would know that by cursing this son of Abraham, Goliath was bringing down the Lord’s curse on himself (cf. Gen 12:3)—a favorable outcome to the battle (from an Israelite perspective!) was thus assured. Finally, Goliath threatened to kill David, dishonor his corpse, and then deny him an honorable burial.

17:45–47 Undaunted by the Philistine’s words, David launched a verbal counterattack. He began by demonstrating that he was not going into the battle ignorantly: he was fully aware of Goliath’s arsenal—“sword, spear, and scimitar” (v. 45; “javelin”). David also proved he was aware of the greatest of his own military resources, “the name of the Lord Almighty, the God of the armies of Israel” (cf. Ps 18:10–12).

Furthermore, David expressed an awareness that Goliath had committed a capital crime by insulting, and thus blaspheming, the God of Israel. According to the Law, any individual guilty of blasphemy—even a non-Israelite—must be stoned (Lev 24:16). Perhaps this was an underlying reason why David chose the weapon he did in confronting the Philistine; even before serving as Israel’s king, David would prove himself to be a diligent follower of the Law and thus a man after the Lord’s heart. At the same time, of course, David’s use of the sling and stone also must have been motivated by the fact that he was skillful in their use and the weapon was especially suited for exploiting Goliath’s vulnerabilities.

As David viewed it, Goliath was outnumbered and would soon be overpowered, for the Lord would fight with David against the giant. In the battle that would occur “this day” (v. 46), the Lord would “hand [Goliath] over” to David; then for his part the young shepherd would “strike [Goliath] down and cut off [his] head.” David’s efforts would not be limited to slaying Goliath; he also would slaughter and humiliate the Philistine army. Yet the Philistines would not die in vain. In fact, their destruction would serve a high theological purpose; it would be a revelatory event by which “the whole world will know that there is a God in Israel” (cf. Josh 2:10–11). Achieving a depth of insight remarkable for a person of any age, young David perceived that the events of this day would give rise to narrative accounts that would reveal the Lord’s power and reality to all who might hear them. Eyewitnesses to the ensuing battle would learn an additional truth from the Lord, “that it is not by sword or spear that the Lord saves, for the battle is the Lord’s” (v. 47; cf. 2:9–10; 13:22; Jer 9:23–24; Zech 4:6).

David, the Lord’s anointed one, discerned a theological purpose in warfare. This perspective is one that must be examined because it is of utmost importance for understanding the mind-set of orthodox Israelites in the Old Testament. For David—and, we judge, for all Old Testament Israelites of true faith in God—armed conflict was fundamentally a religious event. Only when the Lord willed it were Israelites under David’s command to engage in it (cf. 2 Sam 5:19). And when the Lord ordained battle for David’s troops, it was to be performed in accordance with divine directives (cf. 2 Sam 5:23–25). Furthermore, because soldiers were performing God’s work, only individuals who were in a state of ritual purity were to participate in military missions (cf. 1 Sam 21:5). The Lord was the one who gave victory to David and his troops in battle (cf. v. 47; 2 Sam 22:30, 36, 51), and thus the Lord alone was worthy of praise for David’s and Israel’s military successes (2 Sam 22:47–48).

17:48–51 The conflict reached a climax as words ceased and both parties moved toward one another for battle. David was clearly the more dynamic combatant; whereas as Goliath merely “walked” (Hb. hālak; v. 48), David “ran quickly” (lit., “hastened and ran”) to meet him.

David’s weapon of choice against Goliath (the sling) provided him with a tremendous advantage over the weapons at Goliath’s disposal. All of Goliath’s weapons were of value only in close combat; even the giant’s spear, because it weighed over fifteen pounds, could not have been used effectively against an opponent standing more than a few feet away. On the other hand, David could use his sling with deadly force from comparatively great distances. With his youthful vigor and unencumbered by heavy armor and weaponry, David could quickly move to locations from which he could hurl the tennis-ball-sized stones directly at Goliath.

Taking a single stone, David felled the Philistine with facility and deadly accuracy. The rock was hurled with such great force that it crushed the frontal bone of Goliath’s cranium and “sank into his forehead.” In accordance with the requirement of the Torah (cf. Lev 24:16), “without a sword in his hand he struck down the Philistine and killed him” (1 Sam 17:50).

David had achieved a stunning victory over the Philistine. Immediately after Goliath died, David followed the battlefield customs of the day (cf. 31:9) by stripping the dead man of his weapon and decapitating the corpse. These final acts against the giant served as undeniable proof to the Philistines “that their hero was dead.” In shock and confusion, “they turned and ran” in a westerly direction, away from the Israelites.

It’s unfortunate that this dramatic account is considered primarily a children’s story or the basis for an allegory about defeating the “giants” in our lives. While there are many applications of a Bible passage, there is only one basic interpretation, and the interpretation here is that David did what he did for the glory of God. David came to the contest in the name of the Lord, the God of the armies of Israel, and he wanted Goliath, the Philistine army, and all the earth to know that the true and living God was Israel’s God (v. 46). Goliath had ridiculed Israel’s God and blasphemed His name, but David was about to set the record straight. David saw this as a contest between the true God of Israel and the false gods of the Philistines. God wants to use His people to magnify His name to all the nations of the earth.

Message Audio/Video and Outline: https://upwards.church/watch-now/leander-campus-videos

Watch Messages: YouTube-Upwards Church